Light to Dark: A Tribute to Dugald Stermer

Dugald Stermer had his own way of typing people. His take came from the world of art. To Dugald, people were either Dark to Light (like his friend Brad Holland), or they were Light to Dark.

Dugald was a Light to Dark guy.

We met in my studio and I began by talking about hedgehogs and foxes. Then I tossed the ball to Dugald and asked him to elaborate on his own theory of types.

"I've always admired people who seem to pull their work out of chaos," he began. "For instance, Beethoven is dark to light. You can’t pick out the individual instruments in his music. The melody and the power emerge out of a cacophony of sound. Bach, on the contrary, is light to dark. You know: counterpoint, you can hear every note.

"And I’m light to dark," he said. "Literally. I have a white piece of paper and I draw on it. And when I’m finished, every mark I make is visible."

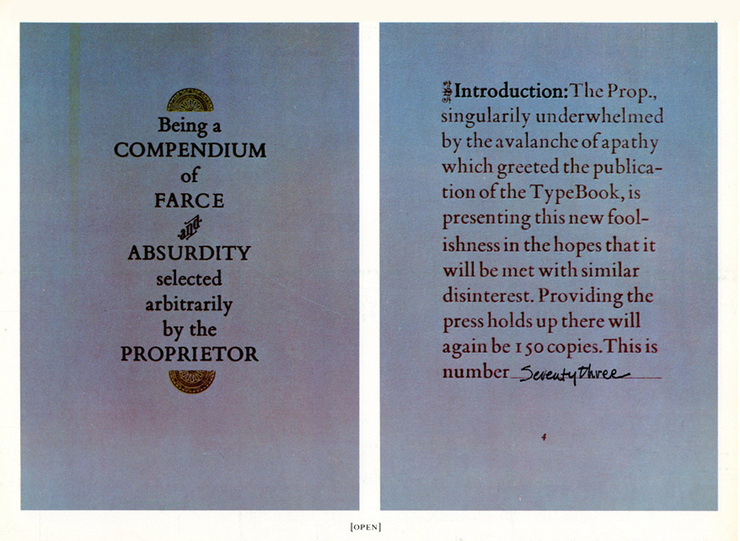

Ramparts was known then – and has been remembered since – as a radical publication. That is, its editorial content was radical. But in its art and design, it more closely resembled a limited edition book.

That was odd. But it wasn't an accident. It was Dugald's personality made visible.

"Stermer’s typography was revolutionary," Ed told Graphis. “[I]t's been copied so often by other magazines, it’s difficult to gauge how innovative and refreshing it was when it appeared."

It was, of course, all those things. But the cliche overlooks the fact that many of the radicals of that time were not trying to tear down the system. They were just trying to see that the institutions that govern society continue to wear a human face. That, in essence, is was what Dugald was trying to do.

As an art director, he helped revolutionize magazine design by picking artists who had something to say, then giving them a place to say it. In that sense he acted as an art editor as much as an art director. That was something new.

For those who don't know, Delancey Street is a residential rehab program that provides housing and work experience in the catering and restaurant trades for ex-convicts, ex-drug addicts and people with no other home in the world. Dugald had his studio in their building on the Embarcadero, although his office seemed to be downstairs at a corner table in the restaurant they ran. At least that's where we always seemed to meet.

Dining there with Dugald was an experience that was inevitably interrupted by the residents who worked there as waiters and cooks. They all knew Dugald and seemed to be fond of him; and spotting him at his regular table, they'd just drop by for a chat.

Over the years Delancey Street has helped so many lost souls find themselves that Dugald was often stopped while eating at other places around town – or even in other cities – by cooks or waiters who had moved on from the program and found work in mainstream restaurants. Having recognized Dugald, they just wanted to drop by, as they once had at Delancey Street, to thank him for the part he had played in reconciling themselves with society.

Dugald was very gratified by this and was probably as proud of his work with Delancey Street as he was of his art. But it amused him that all the ex-cons who greeted him that way seemed to think that he had done time in prison himself.

He concluded that was because he looked like Johnny Cash.

I never knew him to pick a fight, but if a matter of principle turned into one, I never knew him to back away.

He didn't cultivate enemies either. But unless you're a potted plant and are ready to watch cynicism, greed and self-interest steal a march on the better interests of our species, you'd probably better resign yourself to having a few.

Dugald wasn't afraid to have a few enemies – at least not if they were the right ones.

Our mutual friend Steve Heller wrote Dugald's obituary for the New York Times. The kid who had grown up in Los Angeles and dreamed of becoming a cartoonist had left his mark on the world. It was light to dark. And every mark was visible.

I think the same thing can be said about his life.

– Brad Holland, San Francisco 10.12.12

The exhibition of Dugald's work was held at the California College of the Arts, where for years, Dugald chaired the illustration department and where, with luck, his tenure will cast a long shadow.

I want to thank Dugald's daughter Crystal, my friend Robert Hunt, and Alexis Mahrus, the department's Interim Chair, for giving me the opportunity to pay tribute in person to my old pal. They all addressed the audience too and had glowing things to say about Dugald. So did two other longtime friends of his: Eric Madsen and, by video, Steve Heller.

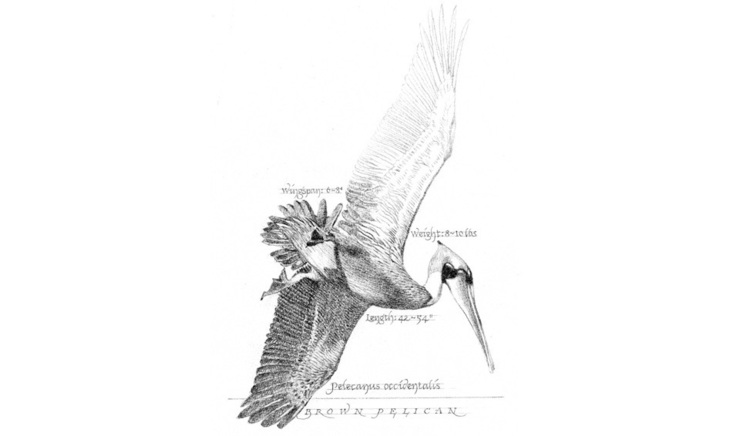

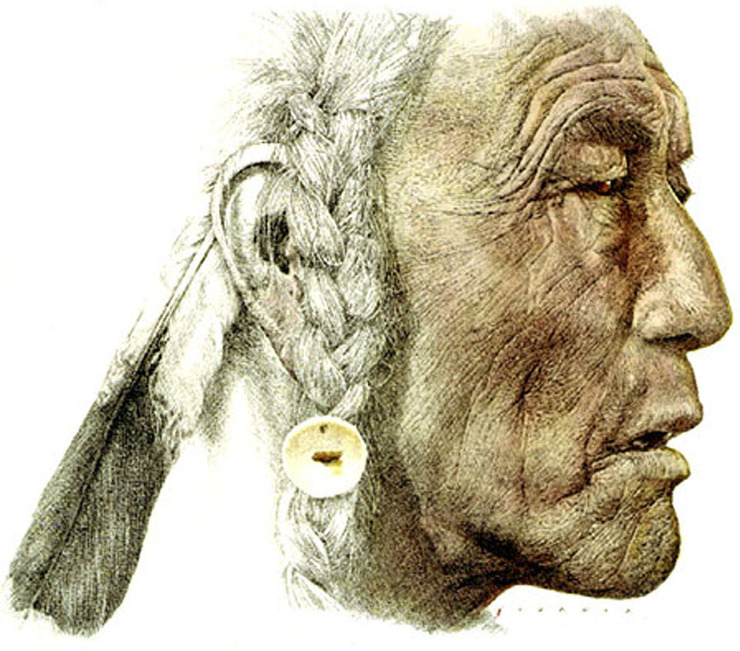

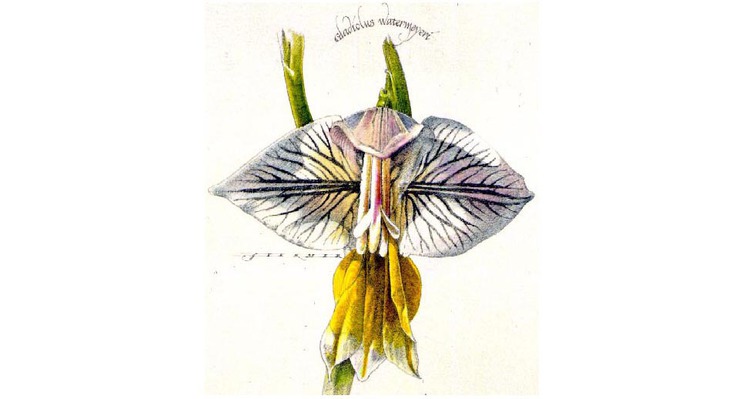

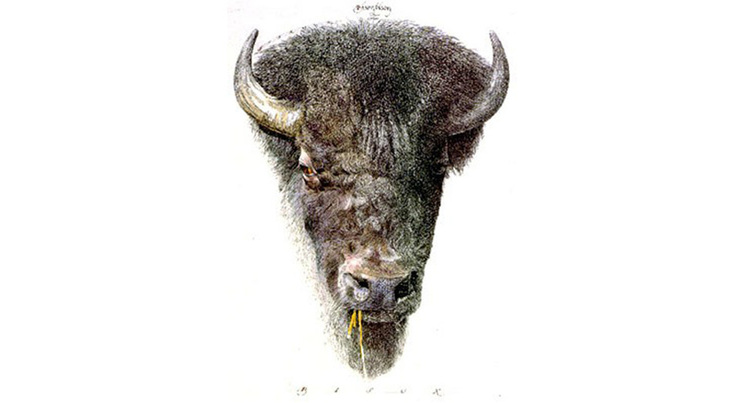

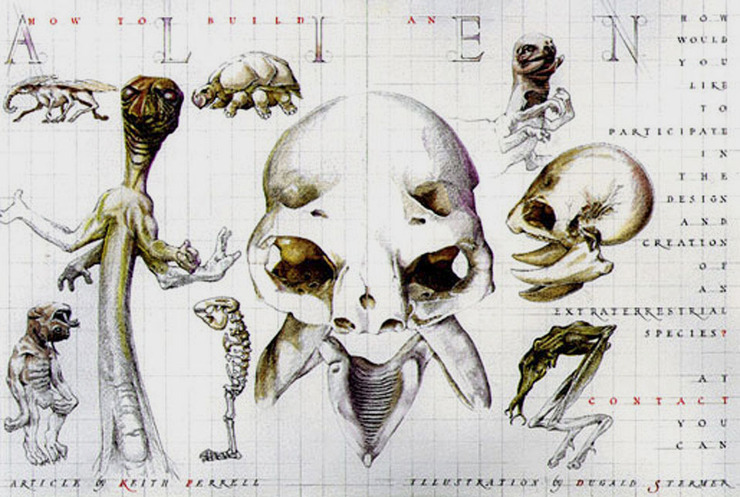

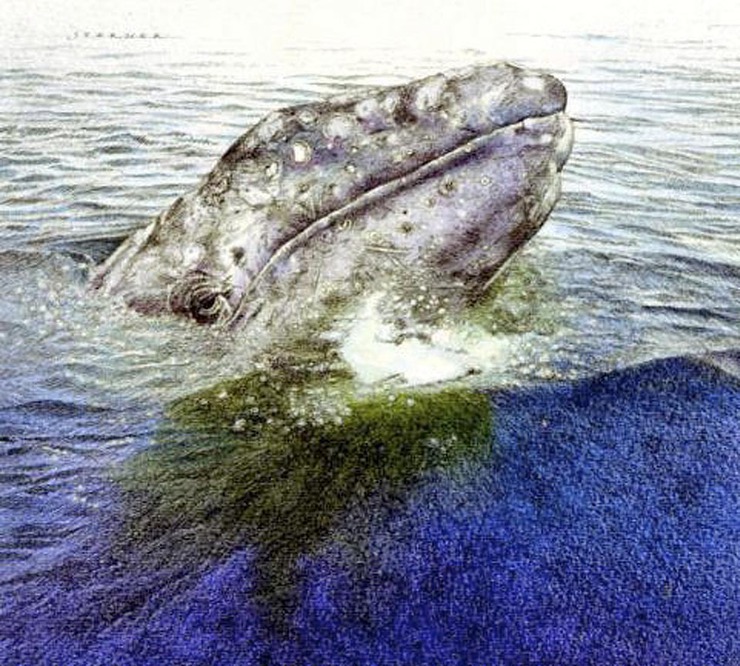

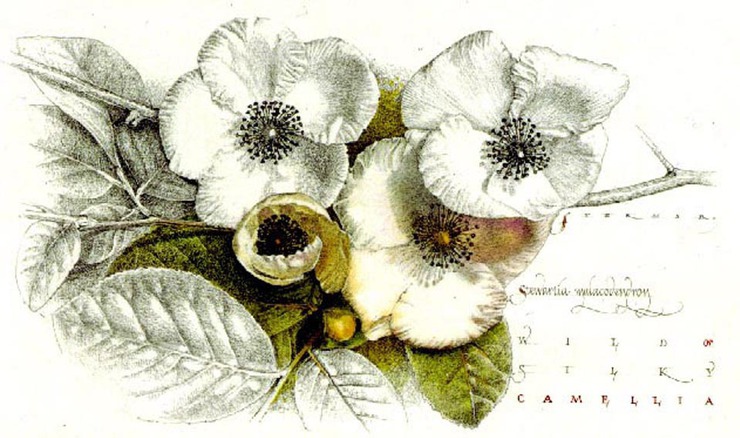

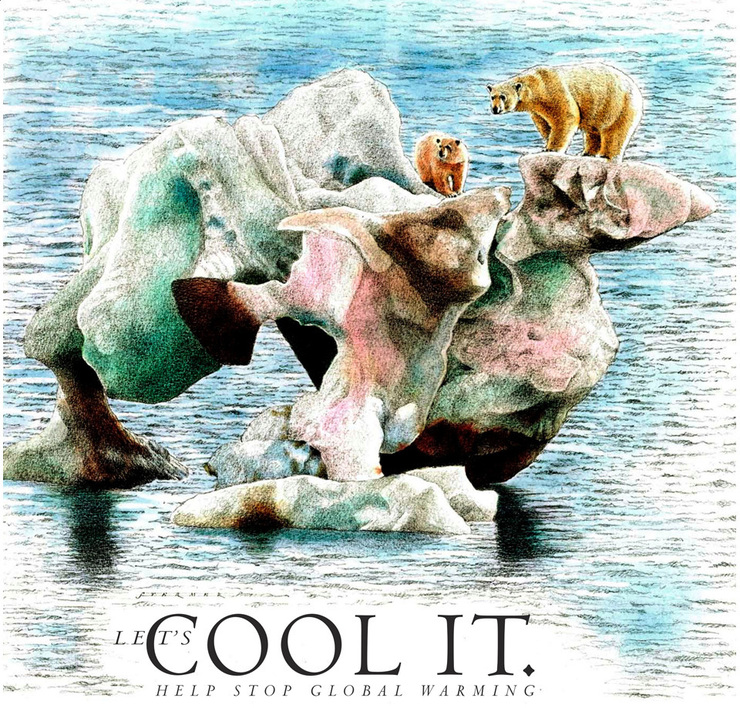

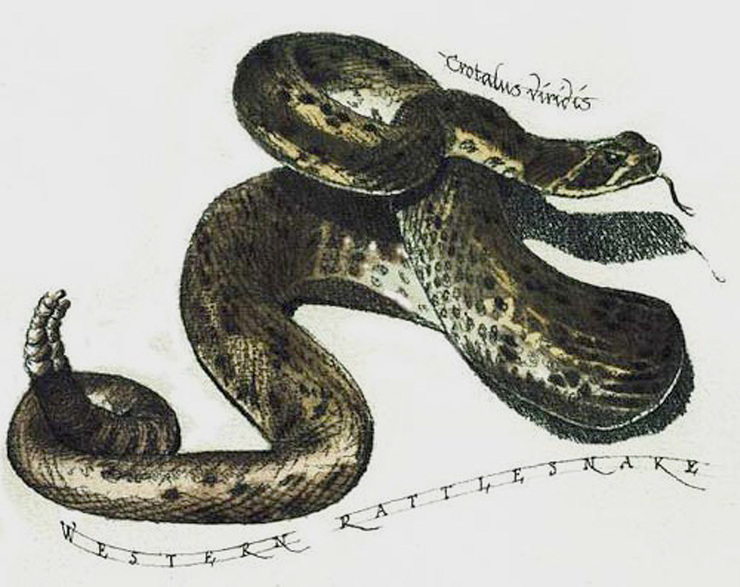

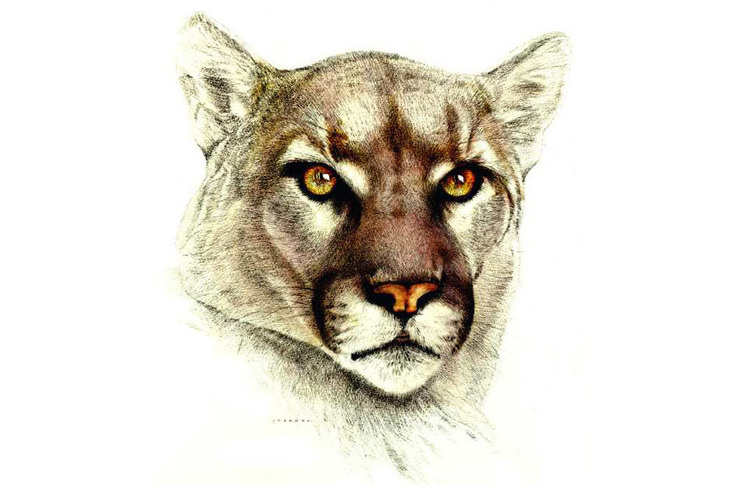

The show was beautifully curated, with examples of Dugald's work from over the years and photographs of him going back to his days at Ramparts. I was particularly moved by some of his first stabs at freelance illustration. He began with a flat and fairly undistinguished form of graphic art, but moved swiftly and with growing confidence into an original style that married design and lettering to his nearly microscopic rendering and came to focus most beautifully on depictions of the natural world.

This style, like his art direction, was Dugald's personality made visible and it constitutes a unique legacy in the history of our field. The best of it is work for the ages and if fate is kind, it'll find a lasting home there.