The Price

I remember back in the early 2000’s after our youngest son, Ben, decided to join the Marine Corps. This was before 9-11. This was before the term ‘cannon fodder’ started getting used again as we ramped up to another war. It seemed a certainty to some that after 9-11 Ben would have a change of heart (he was doing lots of PT with his recruiter but was still in the zone where he could have chosen to drop out). Instead it seemed to solidify his resolve. Friends and acquaintances would ask in conversation, “How could a liberal kind of guy like you sanction a son going into the military?” The answer was pretty short and to the point- he was doing something that gave his life meaning. He was involving himself in something greater than himself. Later on it was “But the war is so wrong.” Well, maybe, probably, but one doesn’t get to choose their battles when joining the military, especially the Marine Corps. It’s a different contract. Many of us in the civilian world, certainly those of us in illustration, have the option to turn down assignments we don’t wish to do. We’ll take them if we need to pay bills but ultimately we have that luxury of choice.

I have posted before about my work in the USAF Art Program, through the Society of Illustrators, drawing, and even painting, service men and women in training for urban warfare, Combat Control operations and Pararescue team exercises. I’ve been fortunate enough, through the auspices of the Troops First Foundation, to travel to Iraq and Afghanistan drawing our men and women of the armed forces, far away from home and loved ones, in harm’s way, in hostile lands and have met extraordinary people with a sense of purpose and conviction that is humbling.

Purpose and conviction, however, take a truly profound test when the ultimate price is paid in the call of duty. The test and burden, in those circumstances fall to the friends and loved ones of the fallen. I doubt few of us have passed through this life so far unaware or untouched by a tragic loss of life in the service of one’s country. The grief is there and it is hard.

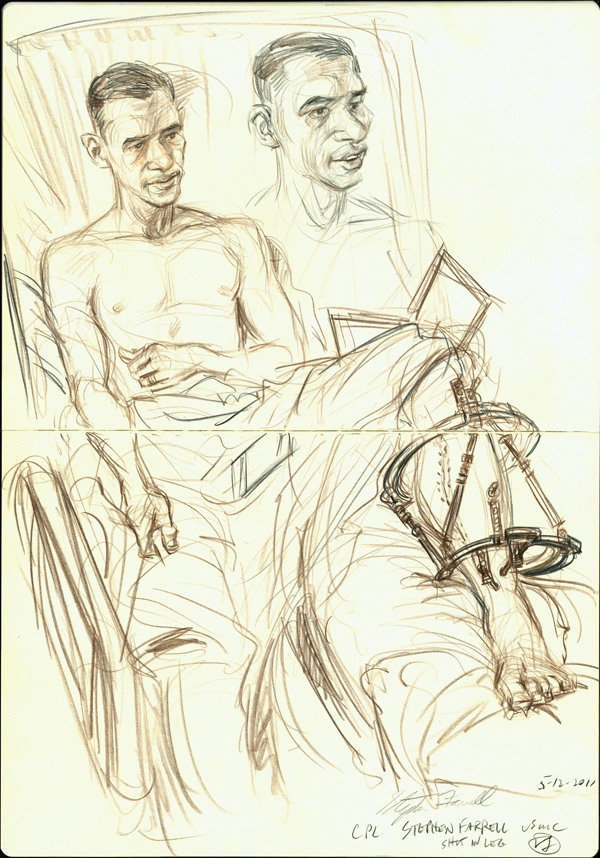

But the mind boggling miracles of modern medical care, of the rapid rescue and treatment of the critically wounded, has delivered many from what even a few years back would have been almost certain death. The test in this growing community of severely wounded is the reclaiming of their lives and sense of contribution to society as they make that long, at times physically and mentally painful, slog through the rehabilitation process. One could assume, and not without good reason, just by the sheer enormity of the challenge that lies ahead for these wounded warriors, that the saving of their lives has been a mixed blessing. I must admit, that ambivalence existed in me.

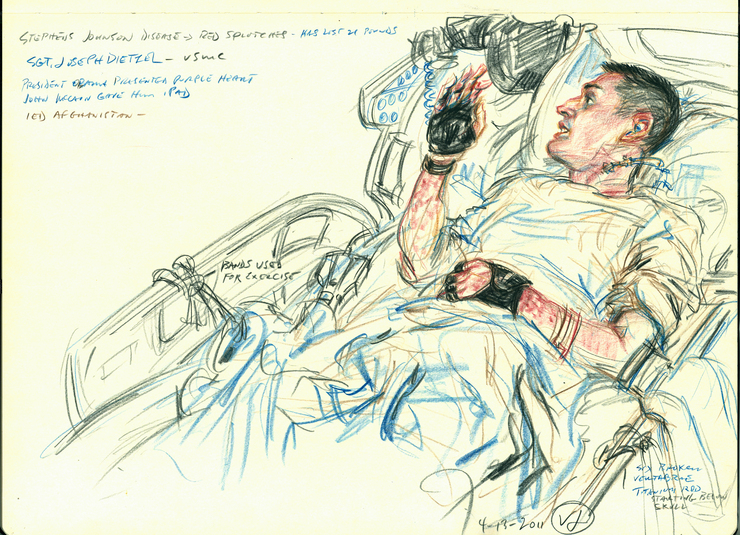

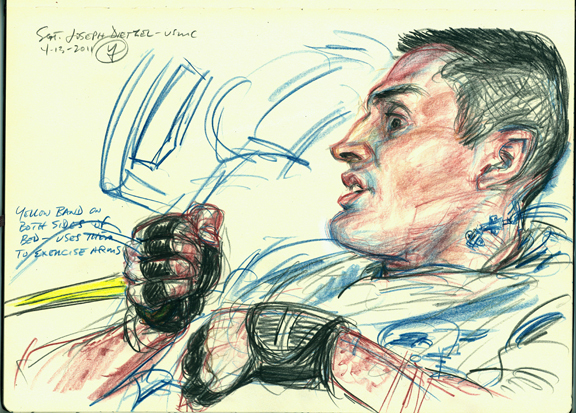

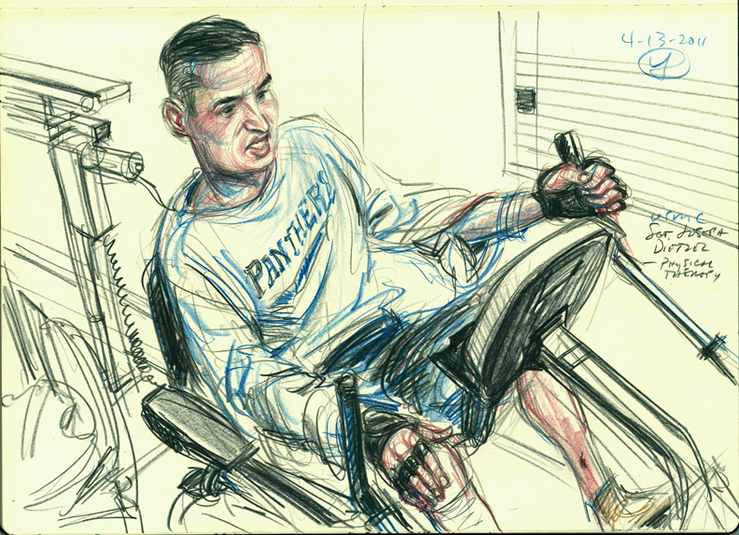

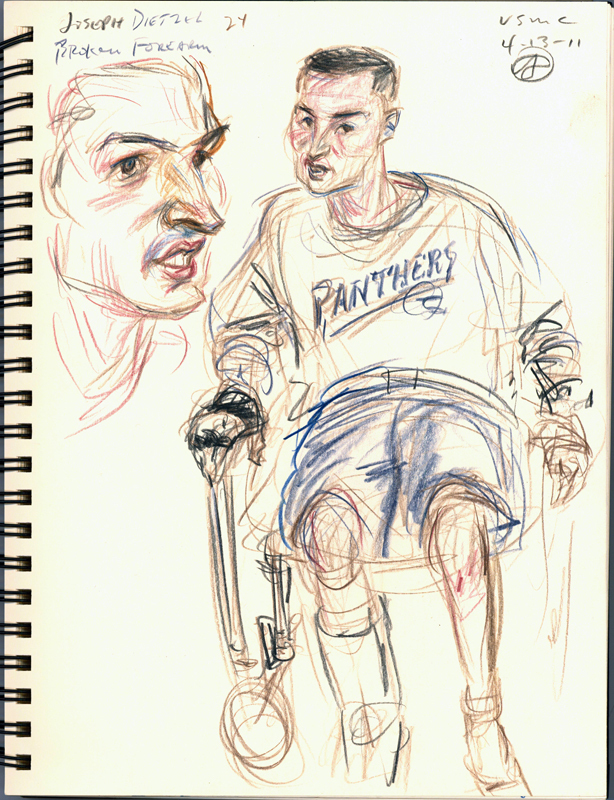

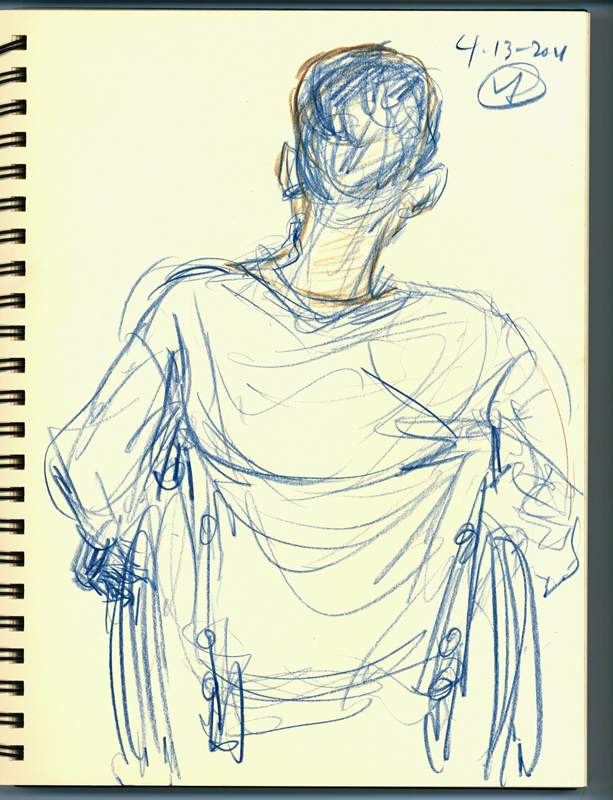

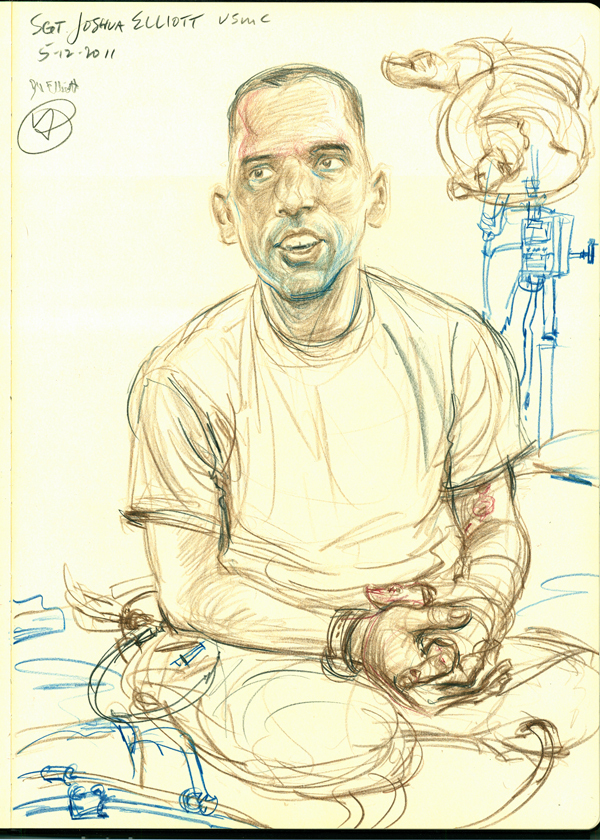

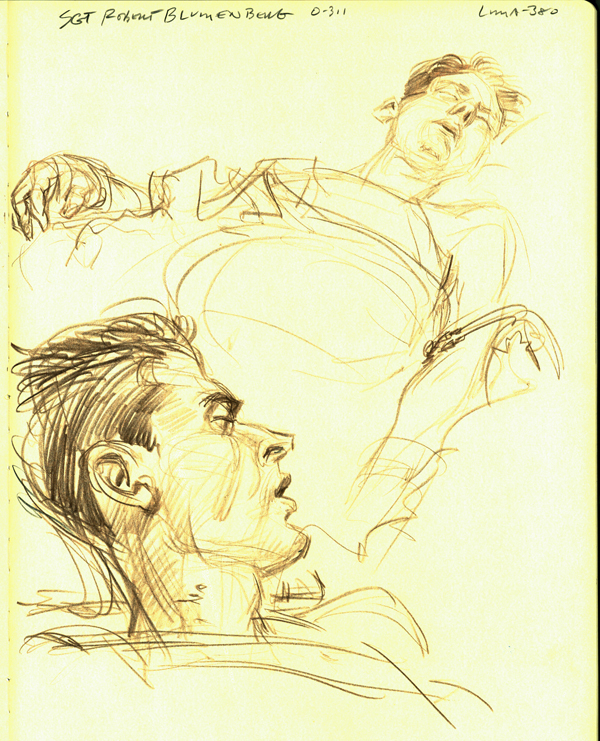

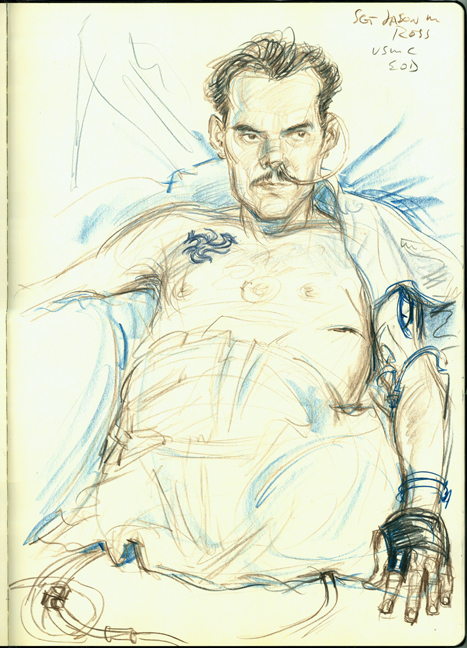

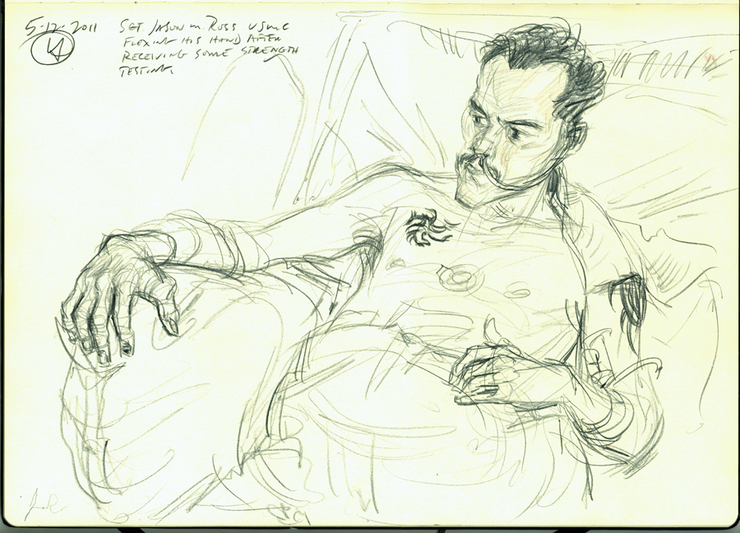

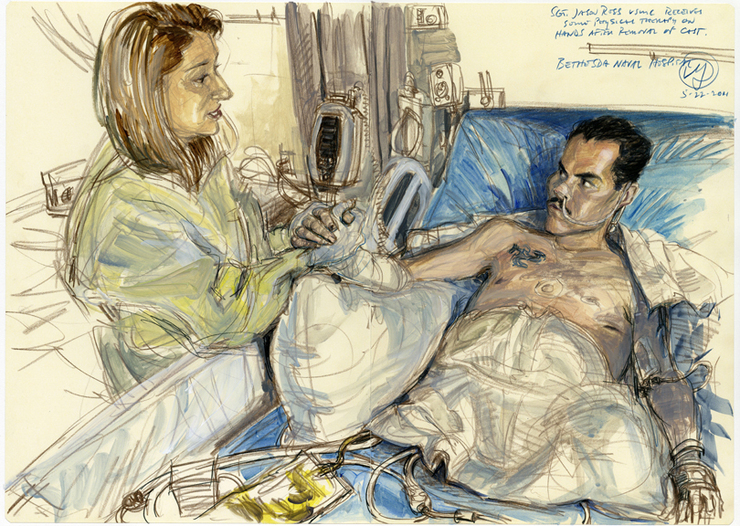

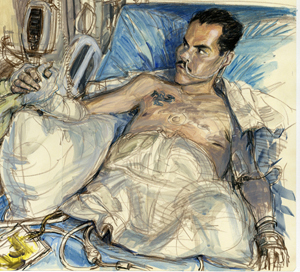

For a few months now I have been involved in a documentation process started by Michael D. Fay, a combat artist and former Marine of over twenty years, of drawing and painting these wounded warriors. It’s called the Joe Bonham Project, named after the tragic character in Dalton Trumbo’s “Johnny Got His Gun”, who is stripped of all his limbs and face, the result of an artillery blast, but retains his mind. By eventually tapping his head in Morse code he communicates that he wishes his reality to be known to the outside world. That wish is denied by the hospital staff. It is an anti-war novel, set during World War I. It is a tragedy. But that idea of rejecting that notion of being hidden away from public attention is what drives the Bonham project. It has gotten the attention of the Smithsonian and the artwork will eventually be part of the historical record of 2 wars, the longest in American history, where the price paid by these warriors has for the most part been a struggle limited to immediate family and friends. The Society of Illustrators has also gotten on board with members wanting to be part of that documentation.

The ambivalence that I mentioned earlier has taken some hard punches to the head the more time is spent listening to the stories of these warriors while drawing them. Most of my subjects have been Marines, as the Marine Corps seems the most open to telling these stories of valor and sacrifice, and their Marines have demonstrated remarkable lack of restraint in sharing their experiences in a matter-of-fact tone that has at times been unnerving, to say the least. No self pity. No “Why me?”. The only concerns expressed were regarding choices made that impacted their fellow Marines, for those left behind outside the wire, and a not uncommon sense of responsibility for not being with their comrades. All this while hooked up to tubes, IVs, catheters, and colostomy bags. Sit with these individuals for an hour- no, a half hour- and you’ll find yourself becoming increasingly ashamed of every minor ache and pain you complain about during the course of a normal, essentially comfortable, day. That phrase about ‘putting things in perspective’ though probably a cliché, is so true. Is the road for these recovering warriors an easy one with a made-for-TV happy ending? No, it will be filled with hurdles both internal and external. But the will to remain in the existential fight makes disappearing quietly into some forgotten darkness not an option.

It’s not just the fault of a culture more interested in ‘reality TV’ than reality. It has been the governmental policy in the course of the past decade to keep these battlefields far from the public mind. Shopping was equated in some perverse way to patriotism and sustaining the ‘American’ way of life and ‘freedom’. The rules about showing video of caskets returning home have just recently been relaxed. A “Warrior Class”, the result of the ending of a draft and the creation of a volunteer army, quickly evolved out of the tradition of ‘citizen soldier’. In short time these individuals became, in a way, a separate entity from the main of society. Their experiences and struggles became less a community concern and more something limited to immediate families.

Ironically, and surveys have confirmed this, the one institution in this country that receives near unanimous respect and admiration is our armed forces. Forget about Congress and the Presidency. Forget about sports stars- overpaid, whiny, and just one step away from jail. Forget about the obsession with celebrities- they’re just disposable fodder to be replaced by the next train wreck waiting in the wings. The members of our armed forces have largely maintained a degree of duty and purpose that so many in our contemporary culture of instant gratification seem to lack.

These drawings are but the beginning of an endeavor to document the sacrifice of our wounded warriors. As we enjoy the barbeques and festivities this Memorial Day let us keep in mind the price paid by a small- no, minute- percentage of our citizenry, who have chosen to serve to protect our country and, as a possible consequence of that choice, pay a price none of us in the civilian world would even wish to contemplate. “Thank you” is the least we can say.