Pararescue Jumpers- the PJ's- Part 1

Last Autumn I was privileged to spend about a week at Pope Air Force Base/Fort Bragg in North Carolina and, as part of the US Air Force Art Program, in association with the Society of Illustrators, draw the instructors and trainees of the Combat Control School. As I posted then, these are the elite, the special ops teams that drop in and secure a location for landings and takeoffs, and establish a base in which they act as the central nervous system of military operations.

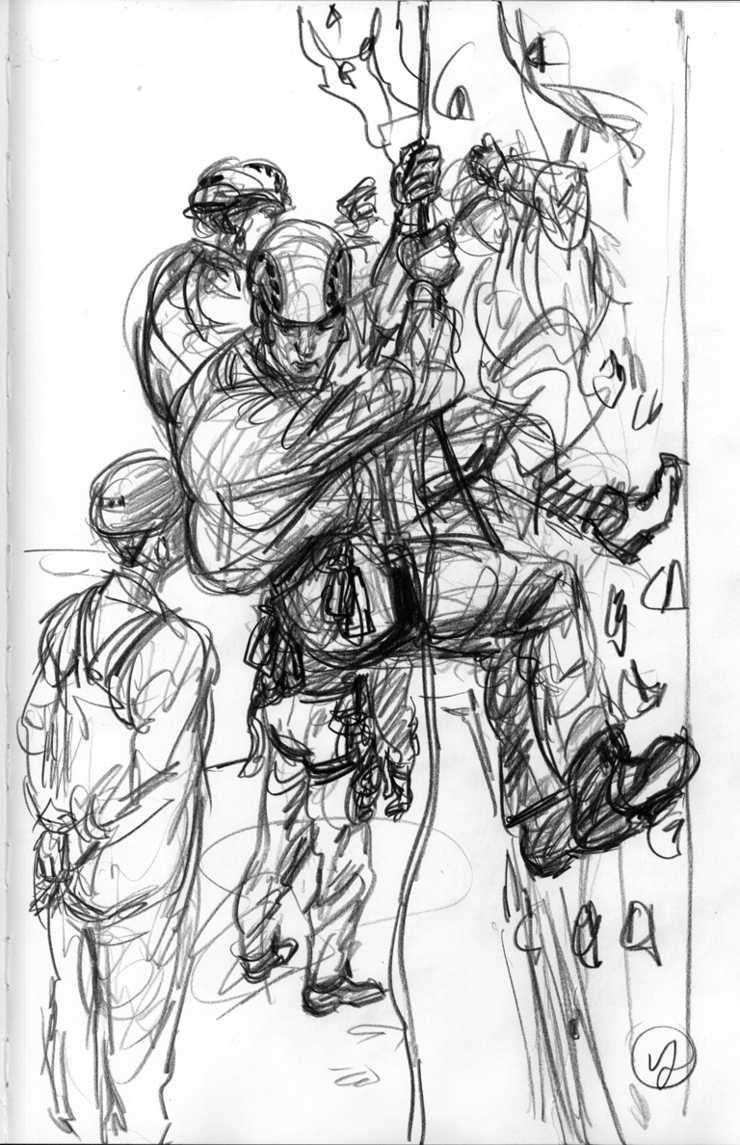

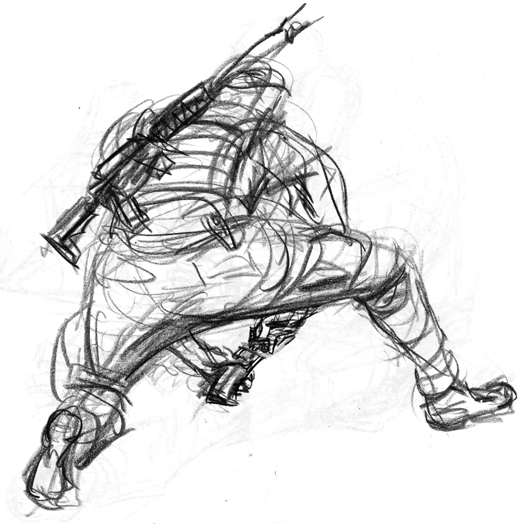

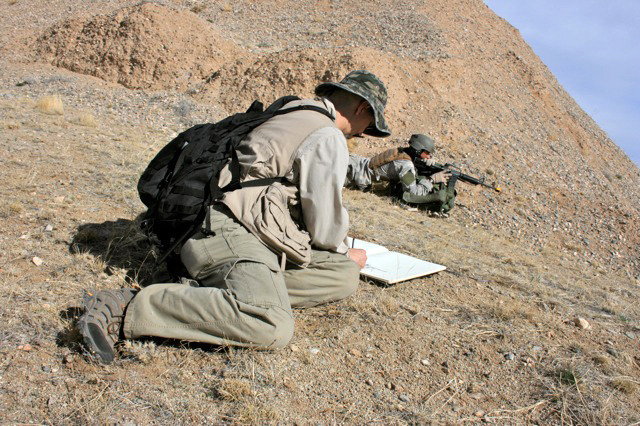

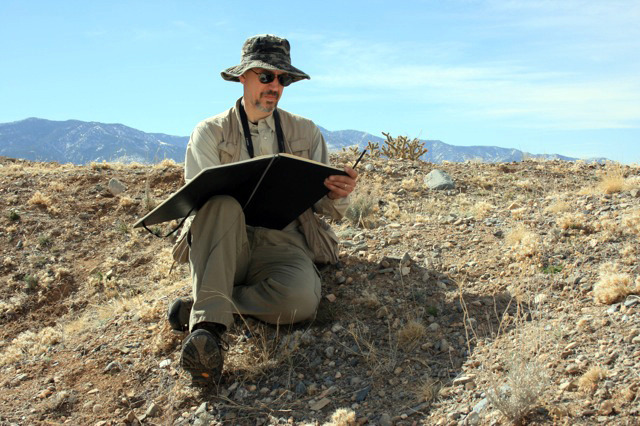

A couple of weeks ago I spent another week as part of the USAFAP, in the company of fellow artists, Bryan Snuffer, Frank Ordaz and Margo Hughes, drawing and photographing instructors and trainees of the USAF Pararescue Recovery Specialist Course at Kirtland AFB in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The mission of the pararescue jumper teams, known as PJ’s, is to recover downed and injured aircrew members, soldiers and civilians in extremely hostile environments on land and on sea. After six weeks of basic military training these trainees spend nearly a year and a half in grueling preparation for these highly dangerous missions of parachuting and diving, searching and recovering. The attrition rate is very high and the pressure is pretty relentless, in both the physical and mental disciplines. After all, extreme combat situations don’t care if you’ve neither slept nor eaten or have had a bad day. They are also trained in emergency medical treatment of the wounded under the most crazy and difficult of conditions for prompt removal to safer locations and more thorough medical attention. The Pararescue jumper teams, an elite force consisting of no more than 600 out of the entire US military, work in conjunction with all the branches of the armed forces and they carry the highest of well earned street creds among the special ops warriors.

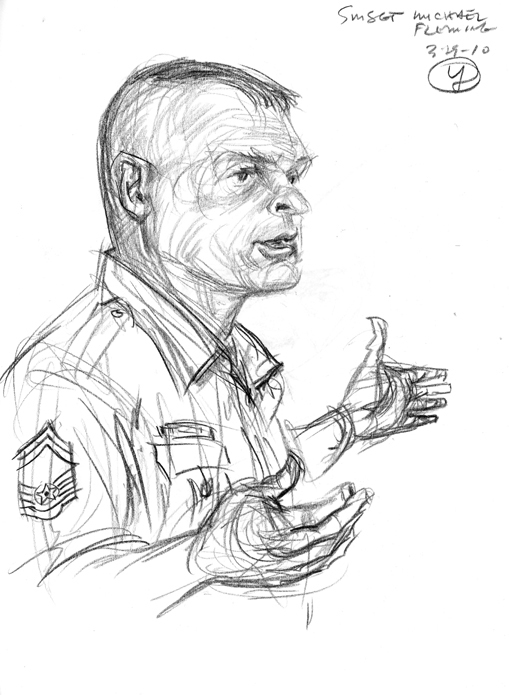

We were greeted by the Commandant of PJ Training, SMSgt. Michael Fleming, who provided us with the introduction to the history and mission of the Pararescue Jumpers.

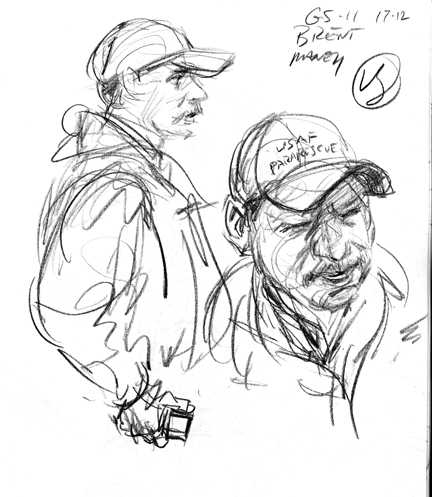

For the rest of our time there, our point man was the civilian trainer, former PJ, Brent Maney, who was responsible for much of the coordination of the events we were able to document. As this was another graduating class in its final weeks, it was remarkable that Brent was able to generously spend the time that he did with us. Frankly, the concentration of Brent and his team of instructors was on making sure this class was going into the actual high-risk operations as fully prepared as humanly possible. As with my observations of the Combat Control Team training, the instructors at Pararescue are incredibly invested in these brave trainees, and work with the utmost sense of commitment and concern, knowing when to mix some humor into the relentless and stressful training. Teamwork is paramount and they are brutally honest in their observations of lapses in coordination and decision making. Obviously it is better to point out the flaws under these circumstances than have them happen under actual critical combat situations. Brent and his instructors seemed to intuit when the trainees were responding more to what they thought their trainers were expecting than acting in real combat thinking mode, and would often change the game plan to throw things off and get the focus back on what was important.

From this civilian’s viewpoint, whether you were an instructor or a student, a type A personality was/is a major plus. Us artistic temperament folk need not apply. Yet, one couldn’t help but be once again impressed and moved by the genuine sincerity and good nature of these individuals. It was an honor to be in their company and witness a small part of what they go through and the sacrifices they make on their way to performing services far above and beyond the expected. “That Others May Live” is the PJ’s motto; it is very concise and accurate, yet only those who graduate the program truly know the gravity and importance of those four words.

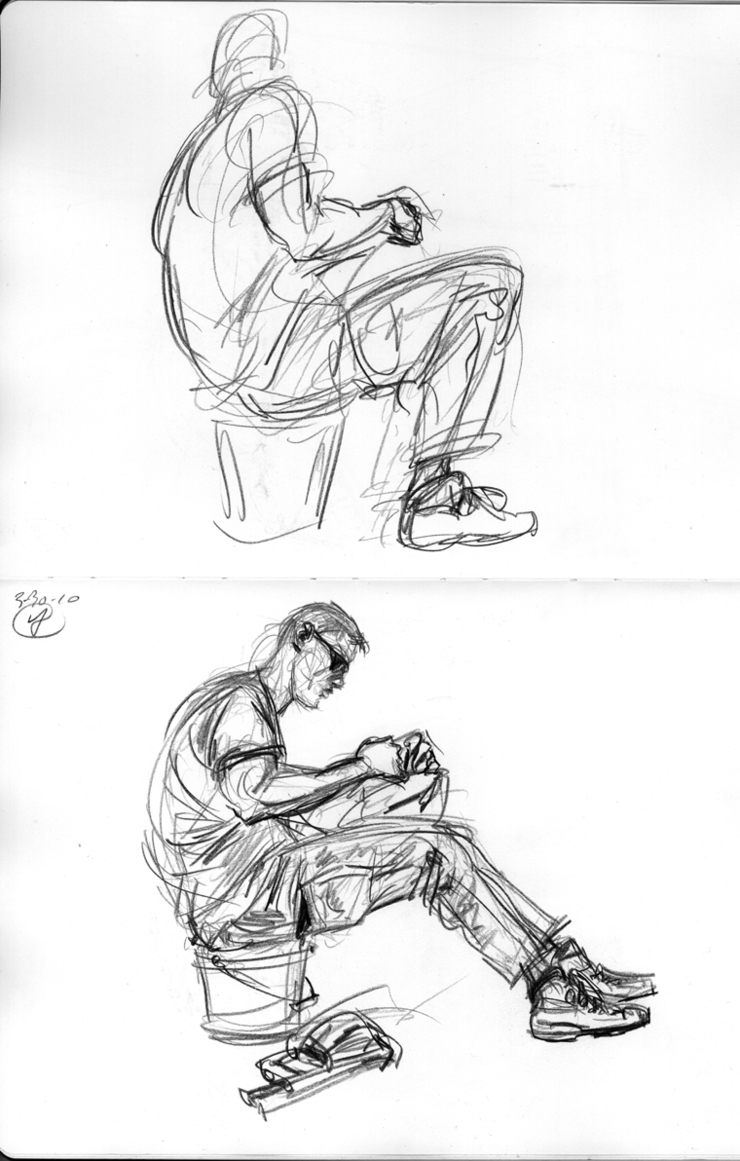

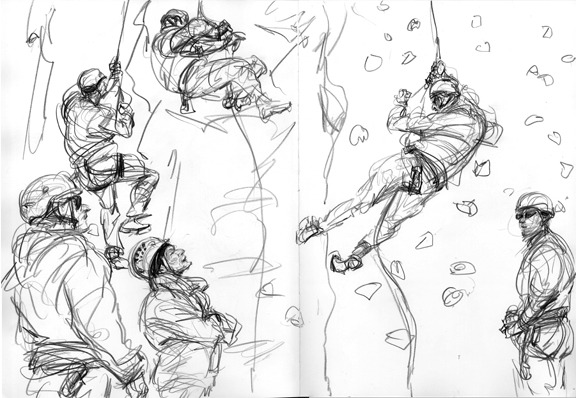

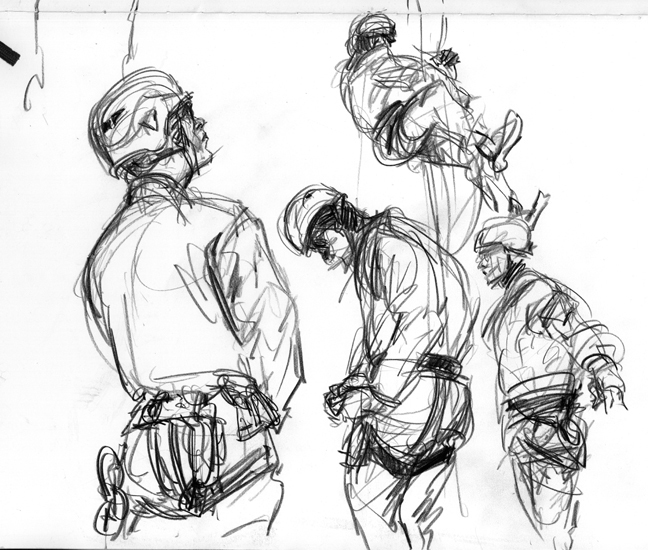

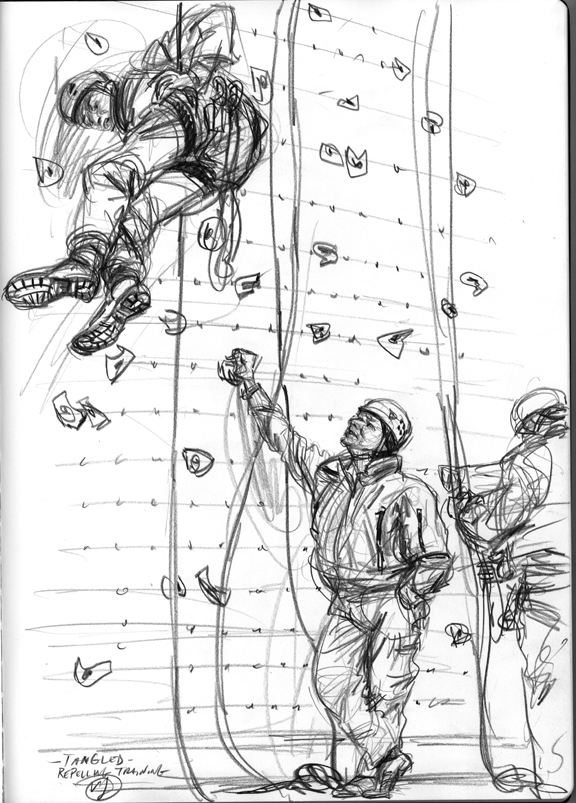

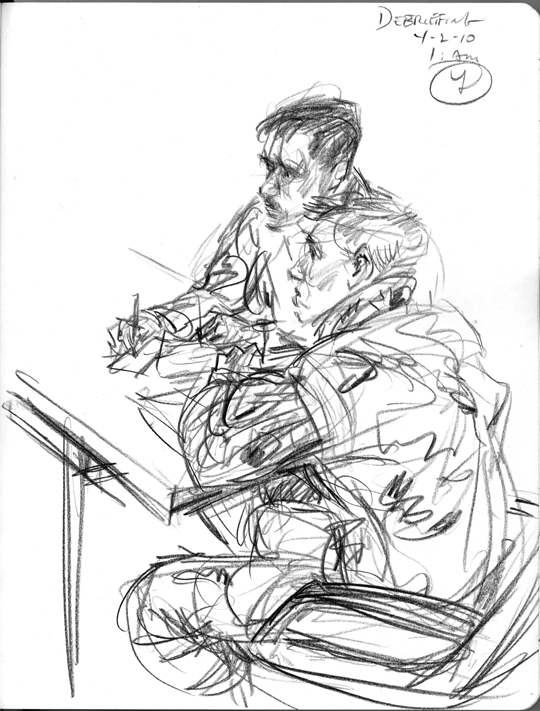

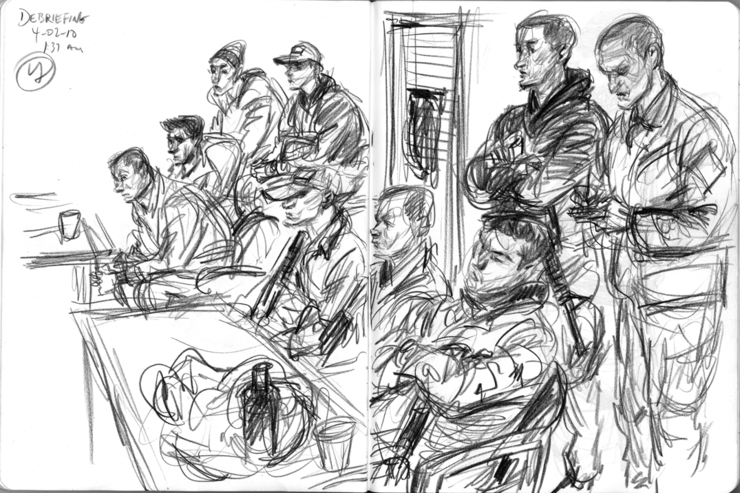

Once again, in situation after situation during the week, trying to catch the fleeting seconds of complicated action on paper, my mind was in a constant awareness and appreciation for the great combat/reportorial artists of the past, people like Howard Brodie and Kerr Eby, who made it look so easy in the middle of actual battle conditions. Sometimes during breaks a student or trainer would walk over and say to me, “I was watching you and how fast you were getting everything down.” I would just laugh and correct them, informing them that they were absolutely terrible models, unable to stay still for more than five seconds. I told a couple about the minute sketches we’d do at the Society drawing sessions, about 55 seconds longer than most of the gestures I was trying to capture. Some turned out pretty good. Most never made it past some stabs at lines describing gestures that were never fleshed out. I suspected that artists like Brodie, who possessed Herculean drawing chops, were also blessed with great memory and could freeze the image in their minds, like a snapshot, if necessary and fill out the details later. I must ask him that one of these days.

With each assignment for the Air Force, I feel I learn something new in terms of handling the pressures. Interestingly, while the intensity and pressures at some of these exercises didn’t were every bit as intense, and probably more so, as on previous assignments they didn’t bend me out of shape like I would have thought. For some reason, I just let the process take its own course and pace and released the paralyzing anxiety of self-judgment. I also was more successful at remembering to use the camera quickly to take backup shots of whatever I was trying to draw, as a photographic memory is not part of my resume. I was grateful to Brent to allow me to witness an extra midnight combat rescue op and ER exercise back at the FOB (Forward Operating Base) when the rest of the gang decided to call it quits for the day. I was beginning to get used to returning to bed at 3 or 4 in the morning and decided to take advantage of the opportunity. Having been through the drill before I had a better feel of where I wanted to be when the action started getting hairy, especially in the ER. A special nod to those trainees who volunteered to play the parts of the seriously wounded in these exercises. Some gave Academy Award performances screaming in mock pain and rambling in semi coherent pleas to their rescuers, which helped greatly in accelerating the sense of chaos in these combat situations. Had I been of sharper mind I would have used my digi-camera to record the performances. I’ll remember to do that next time if the opportunity arises.

There were many sketches done, and while I have no intention of showing all of them, I have decided to break this into two parts. More to come.