It was with a great sense of satisfaction that I successfully mailed out my drawings to the families and loved ones of the soldiers and Marines whom I had the pleasure of drawing. Getting this second set of drawings, and one watercolor, together for this posting, provided a number of opportunities to reflect on the service men and women whom I had the pleasure of meeting and talking to.

I didn’t take copious journalistic notes like Dan Boever, whose postings on his own web page have been real treats to read, if for no other reason than to review the details I missed while intently trying to capture features or gestures of the people I was drawing.

It’s not often that I engage in lengthy conversations while trying to draw my subjects. With the usually short time frame I have to capture a likeness, or likenesses, at any given location, my concentration zeroes in as best as possible on the person, searching for what makes the subject unique.

I forget to talk, make small talk.

What kind of story will the drawing reveal from the marks and lines made as honestly as possible?

That’s always the challenge.

A fellow reportorial artist who also had the good fortune to spend time with Howard Brodie mentioned to me last week that Howard told him,

“Don’t draw what you feel- draw what you see.”

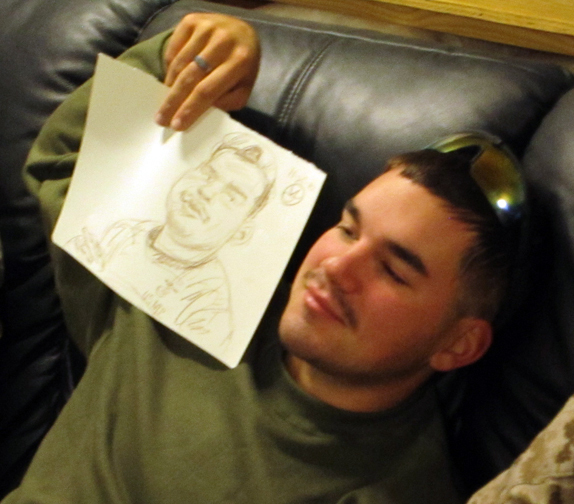

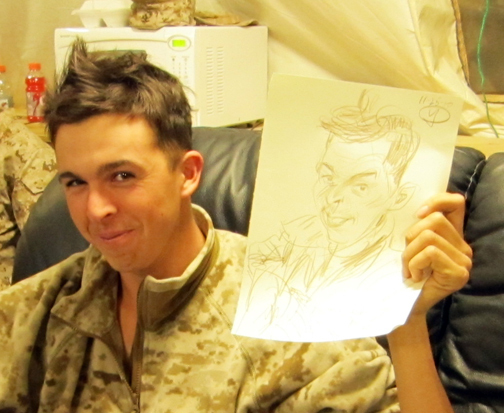

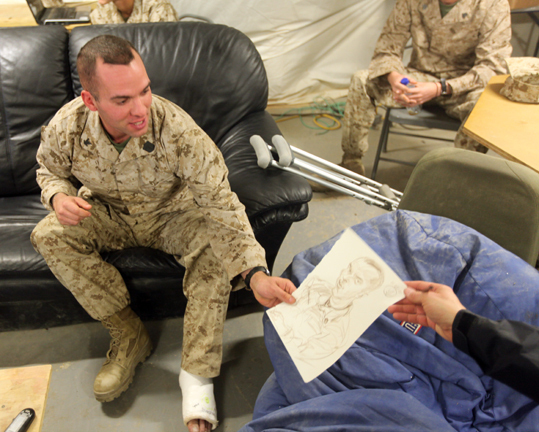

Not having the advantage of observing myself and the nature of the exchange that would go on between my models and myself, it’s easy to underestimate the impact that a mere drawing can make on the subject. Dan Boever would remark to me that the energy and excitement from these soldiers and Marines watching me draw them or their comrades was very different from how they would react to being photographed. Everybody gets photographed. Not everyone gets a drawing done of themselves. Lines and markings on a blank sheet of paper that build into a person, a person you recognize. And you’re watching it happen even as you sit still and maybe get teased by those around you. If memory serves me well, often my immediate area got pretty still as the process was being observed. Apparently there were a lot of smiling faces paying attention around me that I wasn’t keeping track of. The positive effect is compounded if it actually bears a resemblance to the model.

I’ve mentioned it in the previous posting, but so many of these servicemen and women seemed to have come from central casting. They could be movie stars with their chiseled good looks and non-civilian physiques. The Marines as a rule, both men and women, fell into this observation the easiest. So many great character studies. Their naturally genial and polite dispositions, once they started talking, quickly and consistently mitigated any intimidation a civilian might justifiably feel just hanging in their presence. This is not to say they weren’t intense, but it was an intensity that neither threatened nor felt a need to be on display. But you knew it was there from the passion in their conversations.

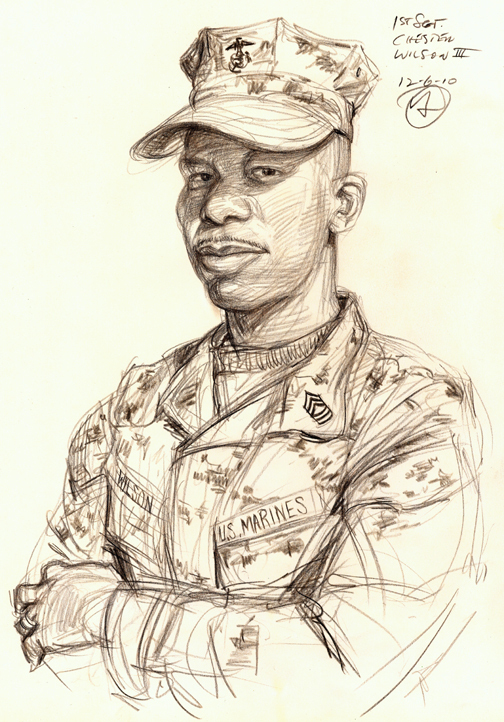

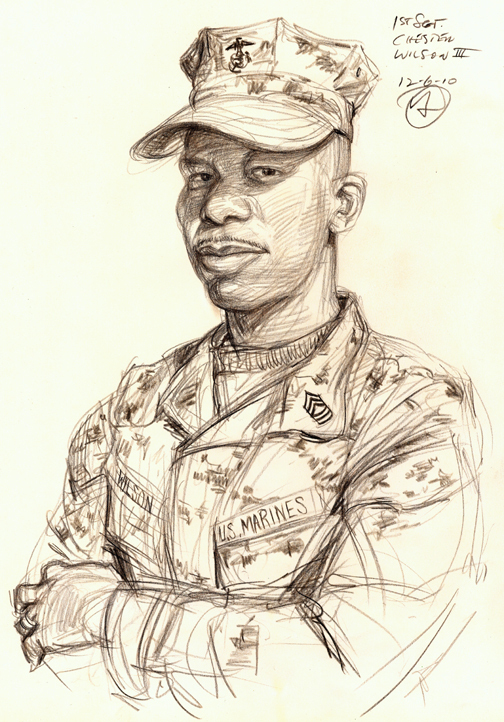

1st Sgt. Chester Wilson had observed me drawing and requested one of himself. We had to move on but I took a couple of photos of him from which I worked after returning home. The result.

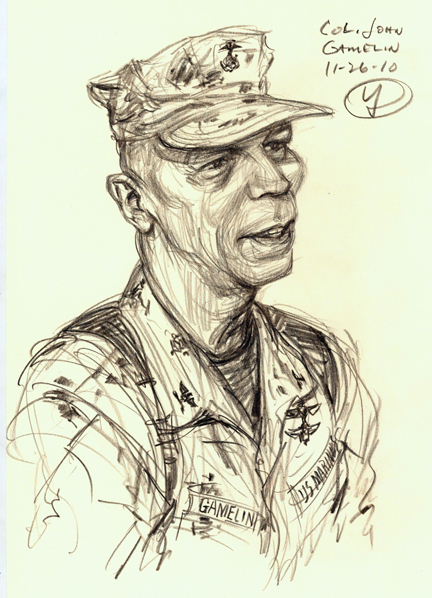

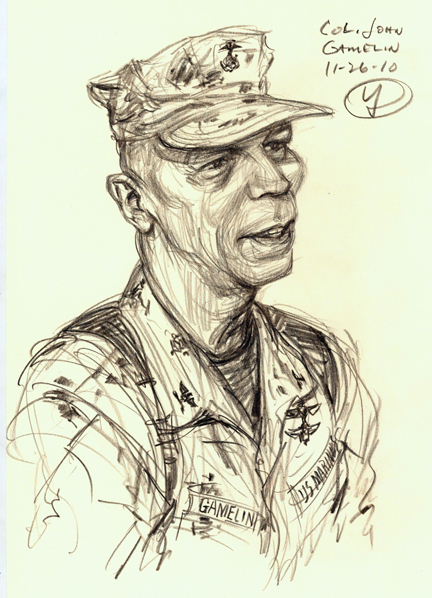

Col. Gamelin was one of several examples of working on an unfinished original back in the studio that started falling apart once the studio lines started to intersect with the spontaneous, intuitive lines done on the spot. So I redid it using some pictures. Backing my drawings up with photo reference has become nearly second nature. Actually, this re-do allowed me to play with textures and skin tones. The Colonel has a great face.

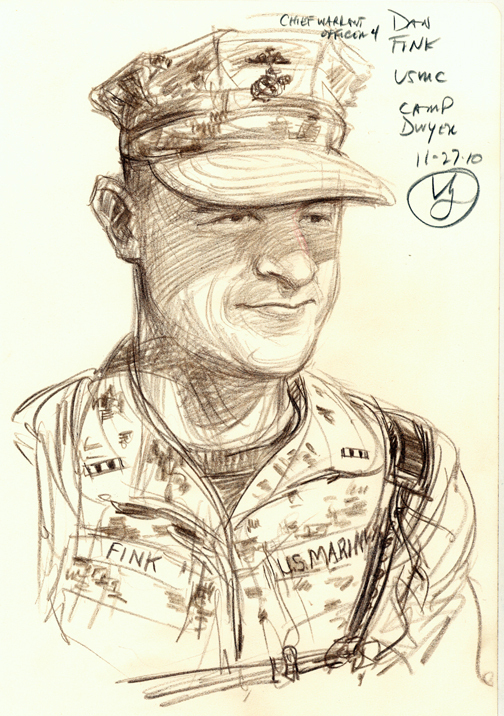

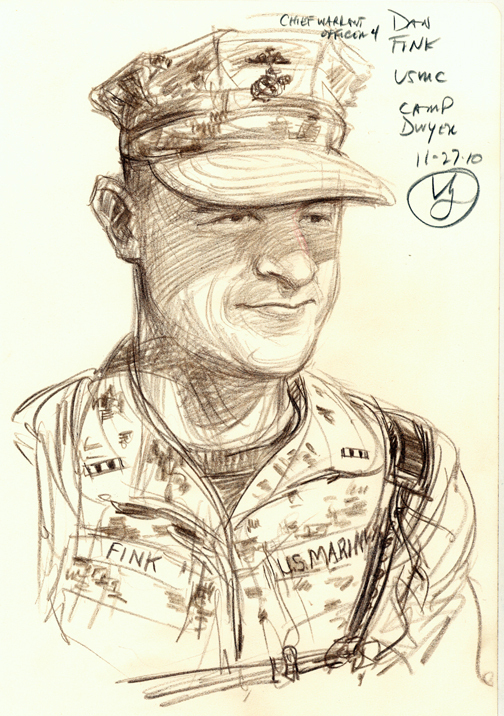

Very very little added after returning home. This is essentially the drawing done in the few minutes I had time. Maybe it really wasn't a few minutes and only felt that way. No matter because CWO4 Dan Fink was a remarkable and game model.

Poor Chief Warrant Officer Fink. He stood like a statue- immobile- in this hot sun. Didn't move any muscle other than his mouth's while he talked to me. A great model and an absolute gentleman. "I've never done this before." he said with quiet understatement. I think he could have held that pose for the rest of the day if necessary. That inner discipline.

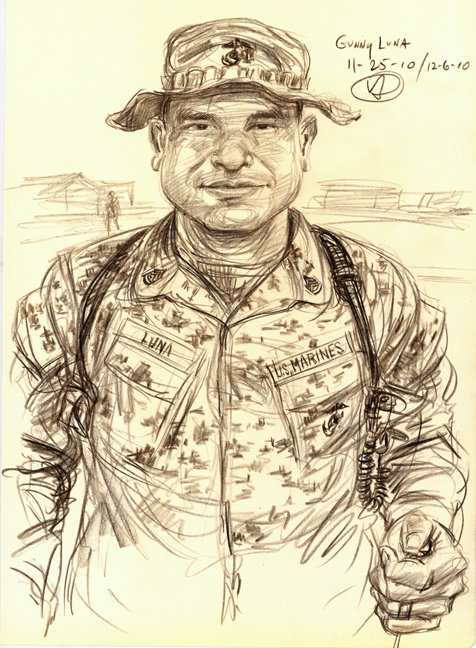

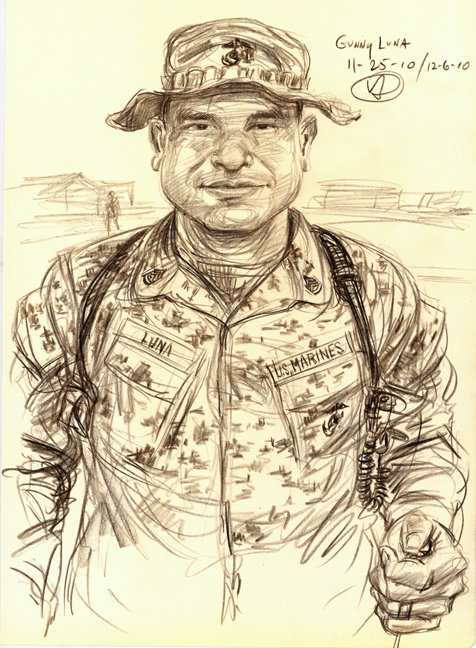

Gunnery Sgt. Luna was such a gentle bear of a man. His fellow Marines kidded him incessantly while I drew.

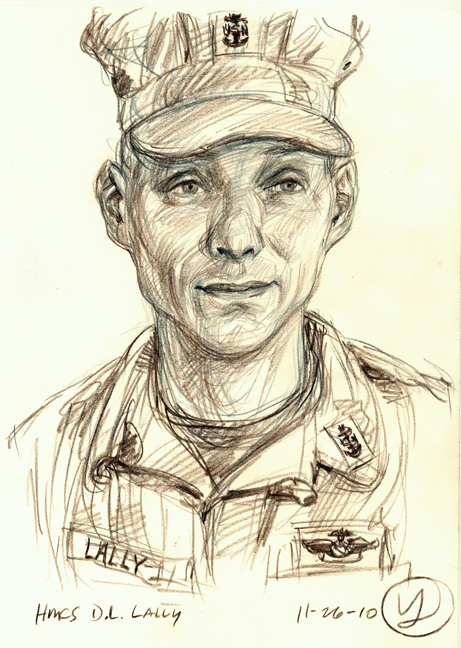

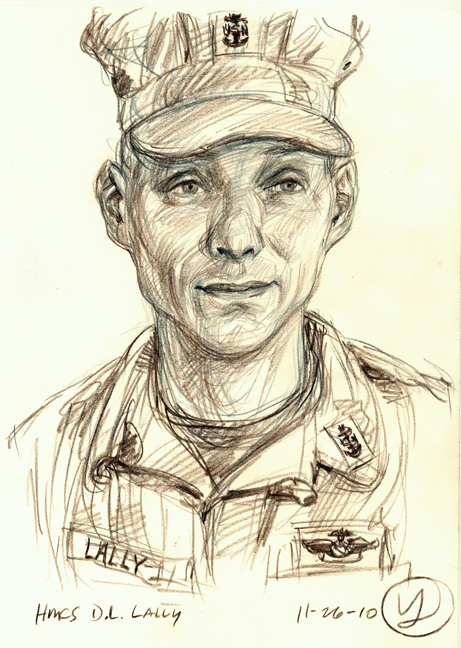

Truly one of the most interesting individuals encountered on this trip. We met David Lally, Senior Enlisted Leader at Camp Bastion's Hospital. He was our guide through the facilities there and, from my point of view, had such a Clint Eastwood vibe to him. I turned to Dan Boever at one point as we were walking around and, nudging him, said, "Pay attention. This is Clint Eastwood." Dan looked at me at first, confused, and replied, "What? What are you talking about?" "Just watch. Follow behind for a little."

Lally explained to us that the hospital facility was second to none with the best trauma unit he could imagine; that the premier doctors and surgeons from around the world came there to work their magic dealing with the most horrific wounds from the theater of combat. Dan Boever's notes record Lally's explanation of the "golden hour"- if the wounded can arrive within 35 minutes the odds on saving them increase immensely. They served not only the military casualties but the civilian population. The hospital ER staff is British; their empathy and concern natural and open hearted, their unflagging good humor amidst the obviously challenging circumstances truly moving. There was a section where donated supplies and personal items were collected to give not only to the wounded warriors but to the civilians, in particular the children. The hospital can always use more donated supplies (warm, comfortable stuff- blankets, socks, gym shorts). I don't feel I am violating confidence here by posting Lally's email if you wish to find out how to contribute something. DAVID.LALLY@AFG.USMC.SMIL.MIL

A tall, lean man with wide, sloping shoulders, Lally spoke in a gentle, secure voice that revealed the huge responsibilities he bore running the administrative side of the hospital. He spoke in genuine awe not only of the staff but of the resiliency of the local population, in particular the children. "My daughter scratches her knee and she's crying for hours. These kids lose a limb and they want to get on with their lives." I found myself curious about how someone with his duties handled the daily stress. He sort of smiled and credited a daily gym workout with maintaining his balance. Even as he spoke to us a med-evac copter was landing with another casualty and we were directed away from the emergency room area to another ward. Obviously, it was the kind of scene I would have really wanted to record on paper.

As we followed behind him, Boever nudged me and whispered in a confirming tone, "Gran Torino."

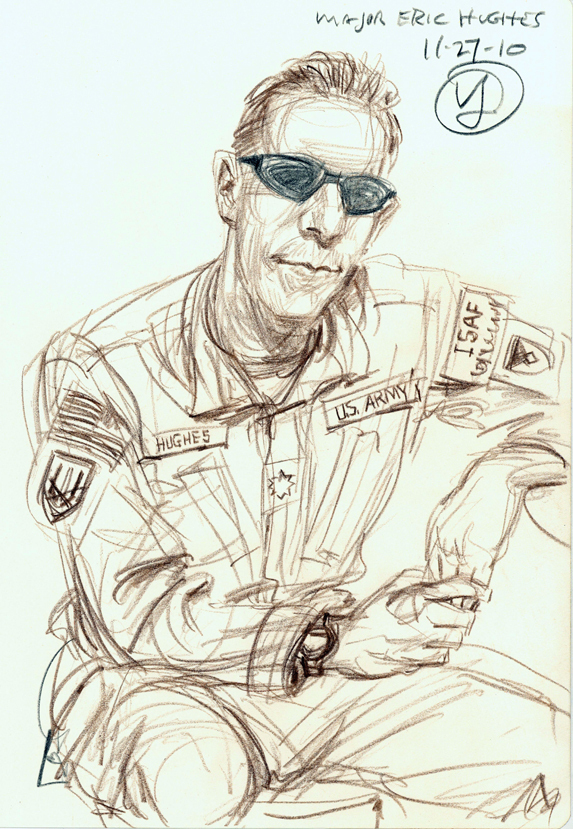

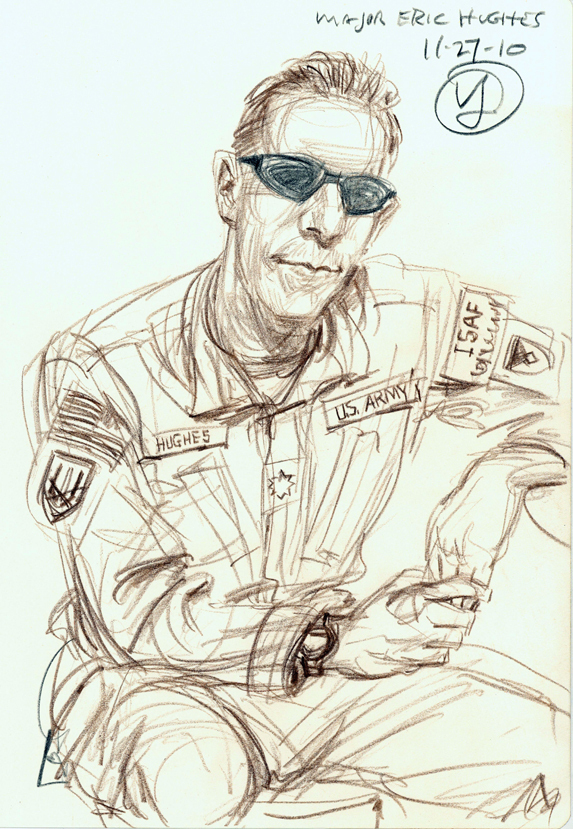

Major Eric Hughes is an interesting story. His mother is a performance artist/dancer. Cultured, smart, very sharp and funny, he's been in the Army for 14 years. I asked him how his mother felt when he joined up. He answered that she felt normal maternal concern but respected his decision. He spoke of the shift that he felt was happening with the local population, and the growing cooperation that's been following as a result, now that the Afghanis feel more certain and secure that we are staying and the Taliban is losing control. It is the common sense of people who are survivors of generations of war. They'll side with whom they sense will be the winner. To my question of what was the message that he felt wasn't getting across clear enough back home he responded, "It takes time. This will not be resolved in a year or two. This is a long term project." And doable as far as he is concerned. Americans, for any number of reasons want things done and done now. We're impatient and that's not an attitude that will allow success in something that requires a long view.

His sunglasses gave him a Richard Belzer vibe in the portrait that I didn't notice till later.

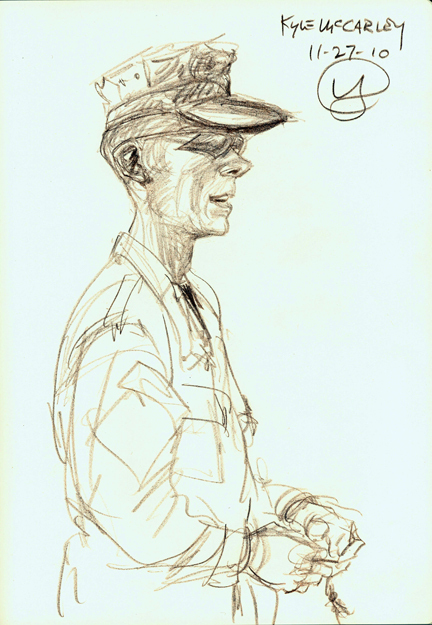

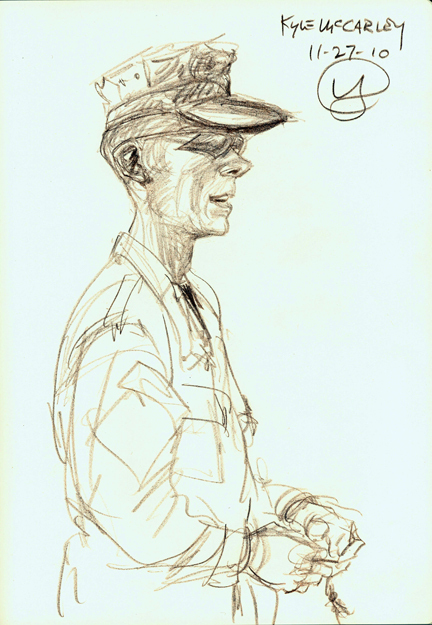

By the looks of the drawing, 2nd Lt. McCarley appears lanky, yet he did his 20 pull ups, without any sway in form, at the bar outside the DFAC prior to entering for lunch. Another one of those very quick drawings that still managed to capture something. Very cool dude.

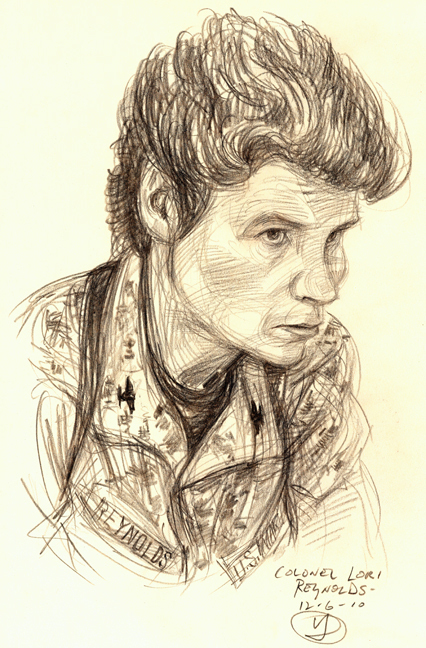

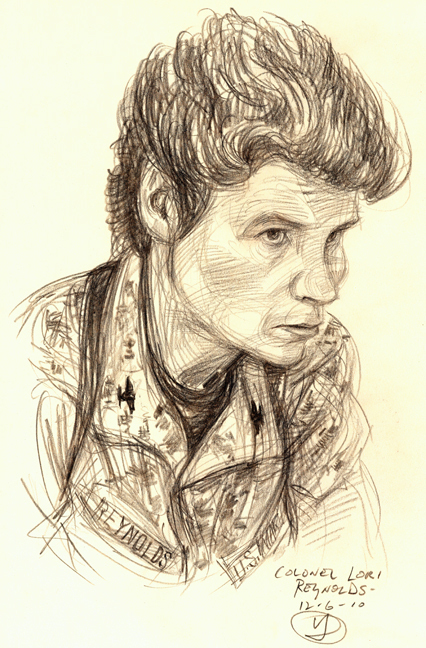

I never got a chance to do a drawing of Col Loretta Reynolds who was our most senior host at Camp Leatherneck. A more gracious and concerned leader would be difficult to find. Given her enormous responsibilities, it was a wonder that she stopped by to check in on us so often. Luckily I snapped enough pictures and was able to work up a portrait back in the studio. I was looking to catch that combination of, dare I say, toughness and sensitivity.

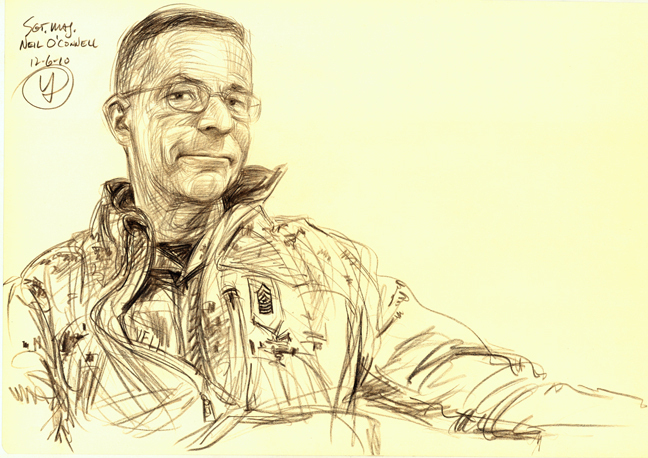

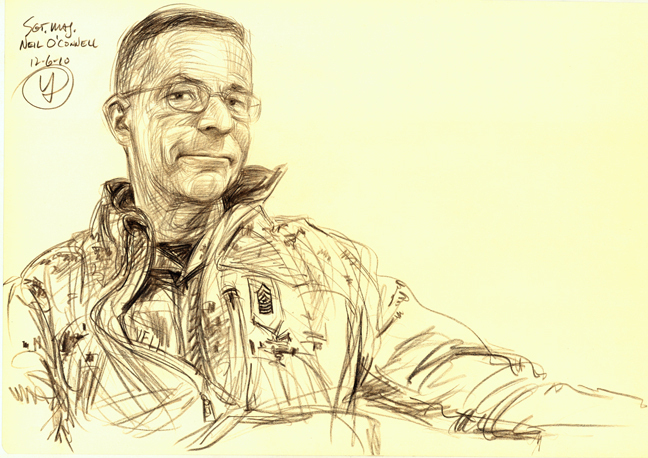

Col. Reynolds' right hand man. Sgt. Major Neil O'Connell. My original drawing was partially destroyed in one of the copter rides. While trying to do another drawing in the windy interior of the copter, the page with his portrait got torn in the violent flapping of the sketchbook pages. Luckily photos saved the day.

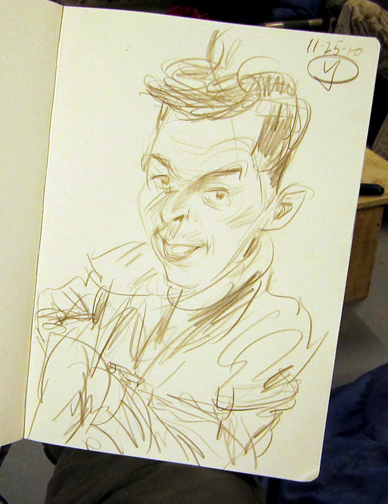

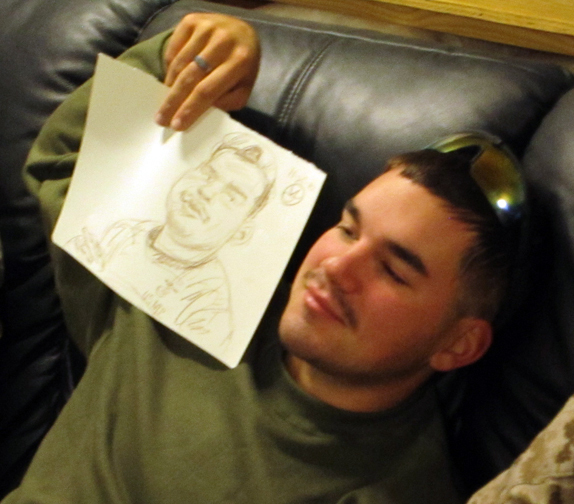

Inside the Wounded Warriors tent. Thanks to Dan Boever for the pix.

Given the circumstances I felt that serious drawings weren't going to add much to the experience. Caricatures seemed to do the trick just fine.

Two guys who originally hailed from New Jersey saying hello. 2 star General Mills and yours truly. Tom Lehman's in the background. Photo by Dan Boever.

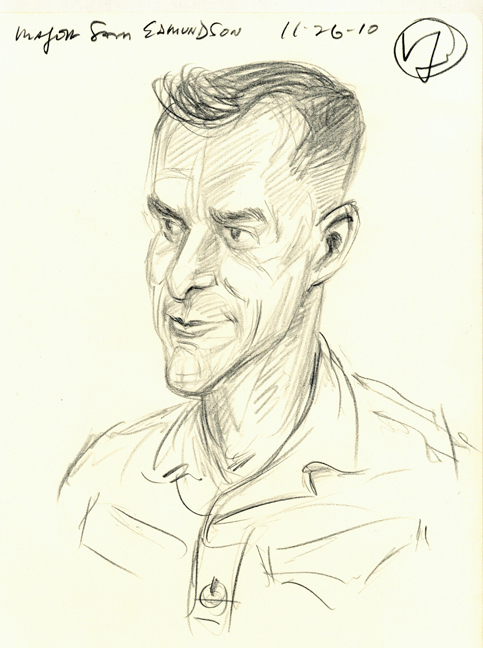

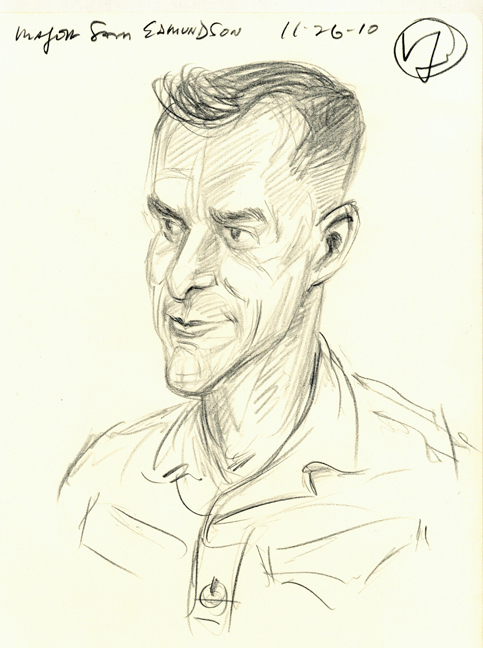

We met a few of the British servicemen and women. All were almost stereotypically charming and ebullient of character. And POLITE, almost to a fault. Major Edmundson, of the Royal Marines, was a striking example of the dashing, chiseled character actor one would find in those great Brit B/W flicks that usually included Trevor Howard. He became very alert that I suddenly started sketching him (very small window of opportunity as his talk wasn't long) and wanted to see the results. The Major seemed very pleased and eager to send the drawing to his father back home.

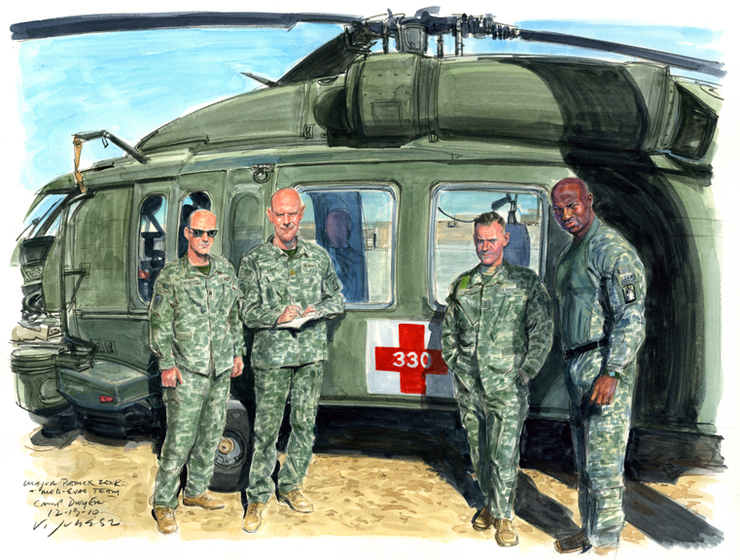

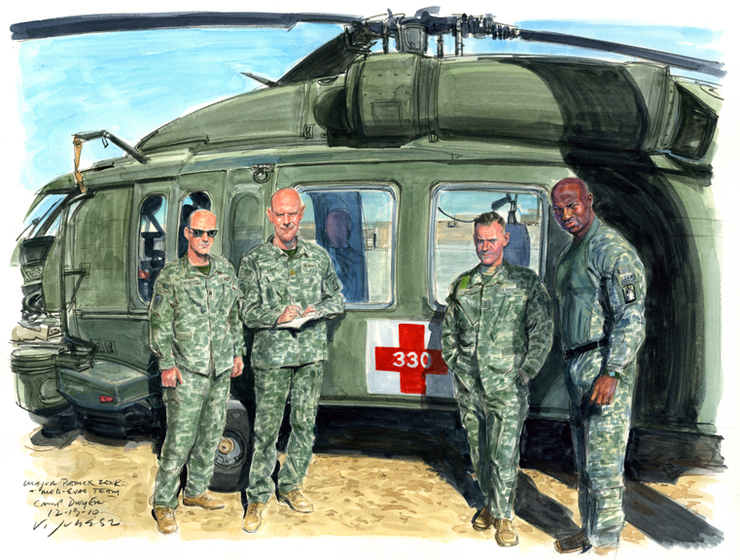

My 'quick study' that turned into a 22"x30" watercolor. Major Patrick Zenk and his med-evac crew. The Army copters handled the rescue operations, landing in hostile fire to rescue and deliver casualties to the base ER's. The Marine unit which was right next door at the airfield would provide the protection from the air with their Cobra copters, very nasty looking machines that pack brutal firepower.

I had managed one drawing at the Army unit, that of Major Hughes, when Major Zenk came walking over looking for me. "Can you just do a quick drawing of me and my crew by our helicopter. Nothing fancy. Just a few quick lines." I thought to myself, "Oh my God, he really thinks it's that easy." I also couldn't refuse this request from guys who are getting shot at on a frequent basis. Yelling to the rest of the gang to wait a few moments, I walked with the Major out to his copter explaining on the way over that a drawing of that complexity takes some time which I didn't have right then, but I would shoot some photos and work something up when I returned home. They posed, making sure the number of their copter was clear to view and I snapped away. Back in the studio it became apparent that in order to get some idea of what these men looked like in front of their machine, the drawing needed to get bigger. Several attempts later I arrived at a respectable size to give definition to their features. It was then that the idea of doing the picture in watercolor overrided any consideration of rendering in pencil. Both high and low resolution files were sent to the Major earlier this week and the crew was very happy and grateful.